Plastic is a material that is used in just about everything — packaging, consumer goods, toys, cars, etc.

The trouble is, massive amounts of it end up in the ocean. It does not biodegrade and it contains toxins – breaking up into smaller particles, animals consume the plastic and the toxins then move up the food chain, ultimately to us, humans. But the larger plastic debris pose dangerous risks as well — often ensnaring animals as they swim through the water and, in many cases, causing death.

Studies have shown that about 700 species have encountered marine debris, and 92 percent of these interactions are with plastic — 17 percent of the species affected by plastic are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

However, the larger plastic debris pose dangerous risks as well —- often ensnaring animals as they swim through the water and, in many cases, causing death. Studies have shown that about 700 species have encountered marine debris, and 92 percent of these interactions are with plastic. 17 percent of the species affected by plastic are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

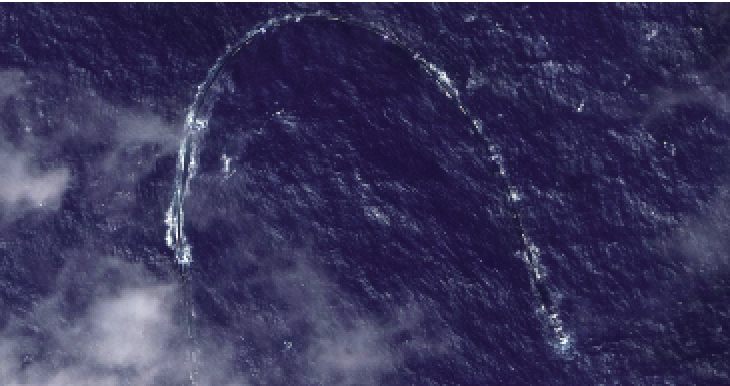

The Ocean Cleanup system being towed out of San Francisco Bay on September 8, 2018, as imaged by Maxar’s WorldView-3 satellite.

The Ocean Cleanup system being towed out of San Francisco Bay on September 8, 2018, as imaged by Maxar’s WorldView-3 satellite.

Tons of this plastic have accumulated in five ocean accumulation zones, also called gyres, where converging currents create vortexes of persistent plastic. These patches exist across thousands of miles collecting trash. The most notable one is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch between Hawaii and San Francisco in the North Pacific.

This is a worldwide problem of huge proportions. So much so that in the last episode of “Blue Planet II,” David Attenborough gave a harrowing speech about the impact plastic is having in marine life. He closed his speech by saying ‘The future of all life now depends on us.’

Indeed, it does.

Dutch entrepreneur Boyan Slat founded The Ocean Cleanup in 2013. Today, Boyan has a team of more than 80 people developing advanced technologies to rid the world’s oceans of plastic. And we’re now working with Maxar to use its high-resolution satellite imagery to help monitor and improve The Ocean Cleanup’s efforts from space.

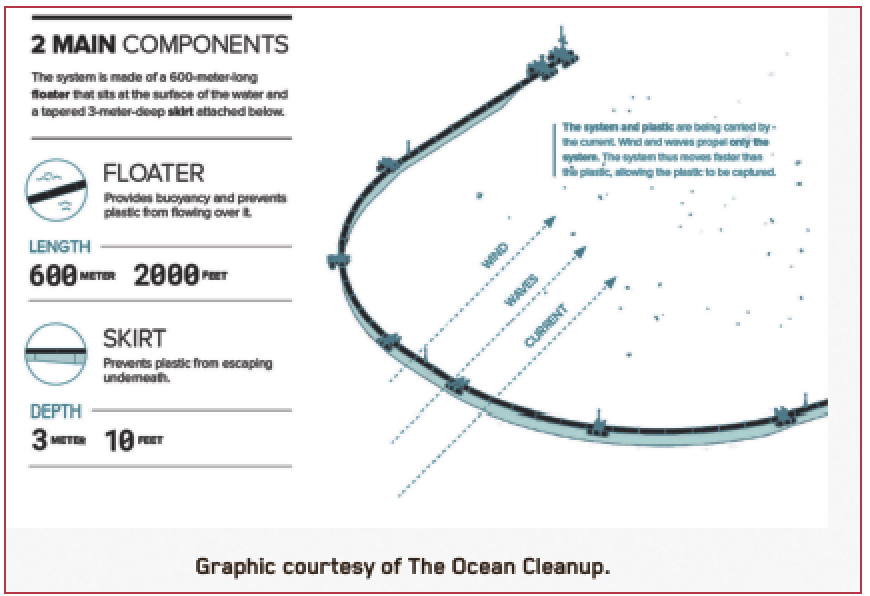

Collecting plastic from the ocean using vessels and nets would be costly, time-consuming and damaging to the environment. That is why The Ocean Cleanup is developing a passive cleanup technology, which moves with the currents —just like the plastic itself — to collect it (the infographic on the next page shows the system).

The Ocean Cleanup launched a beta system, System 001, from San Francisco in September 2018. During its deployment, many key features of the technology were confirmed, such as the system’s U-shape configuration, its ability to orient with the wind and follow the waves, plastic accumulation and the system’s electronics for navigational safety, status monitoring, and satellite communication.

It was also observed that plastic was not retaining in the system; while adjustments were being tested to solve this, the system experienced a structural malfunction, which required the system and the crew to return to shore. Using the learnings from System 001, a root cause analysis was performed, and design updates were implemented on a revised version of the technology, dubbed System 001/B.

After only four months of design, procurement, and assembly, The Ocean Cleanup returned to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch with System 001/B to test modifications that address the challenges faced with System 001. By adding a parachute to slow down the system, System 001/B did effectively collect and retain plastic — therefore, solving the main challenge of plastic retention and confirming the foundational concept of using natural ocean forces to clean up floating plastic debris.

Although there is still much more work to do, this was a promising result from the trials. The aim going forward will be to start designing System 002 with a focus on long-term survivability and plastic collection.

Meanwhile, System 001/B is still operating about 1,250 nautical miles off the West Coast of the U.S. During its deployment, the system is monitored by offshore teams in a nearby vessel, but it is essential to analyze the system from multiple viewpoints.

That’s where Maxar’s high-resolution satellite constellation come into play. Maxar images the system almost weekly. The Ocean Cleanup team uses those images to monitor aspects of the system’s performance and to make necessary adjustments.

WorldView-3 image of The Ocean Cleanup’s System 001 in the Pacific Ocean.

WorldView-3 image of The Ocean Cleanup’s System 001 in the Pacific Ocean.

With these images, we can track the direction of the system, how much debris has accumulated within it and, when this is applicable, determine the optimal time to dispatch a vessel for extracting the trash from the system.

Because The Ocean Cleanup develops its technology in fast iteration cycles, this is a natural progression on the road to achieving the right design. System 001/B is smaller and modular, so many updates can be made offshore, speeding up the iterations and helping the team learn at a quicker pace. WorldView-3 image of The Ocean Cleanup’s System 001 in the Pacific Ocean.

The second main objective of this proof of concept is to assess the capability of Maxar’s WorldView-3 short wave infrared (SWIR) sensor to detect plastic accumulation within the system.

This sensor is sensitive to the patterns of SWIR light reflected from materials on Earth, so it could inform The Ocean Cleanup team if there is plastic, metal or painted materials in the system.

That information can then be used to monitor changes in debris type, plan for recycling and reclamation efforts and study long-term trends in discarded materials.

Maxar’s high-resolution imagery provides these key insights to The Ocean Cleanup team, allowing an optimal understanding of this new trash-collecting technology, and to reduce the costs of keeping a crew with the system 24/7 in the future.

Maxar is excited to contribute to The Ocean Cleanup’s efforts to rid the oceans of plastic as this effort is closely aligned with the company’s stated purpose, For a Better World.