Curt Blake, Senior Columnist, and Sophia Galleher, Senior of Counsel, both with Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati

Recent breakthroughs in launch technology and high-efficiency solar cells, combined with the potential for large-scale, in-orbit maintenance and construction, have revived serious interest in space-based solar power (SBSP), a long-touted but cost-prohibitive and technologically infeasible method of power generation as the answer to the urgent and growing demand for renewable energy.

Understanding Space-Based Solar Power (SBSP)

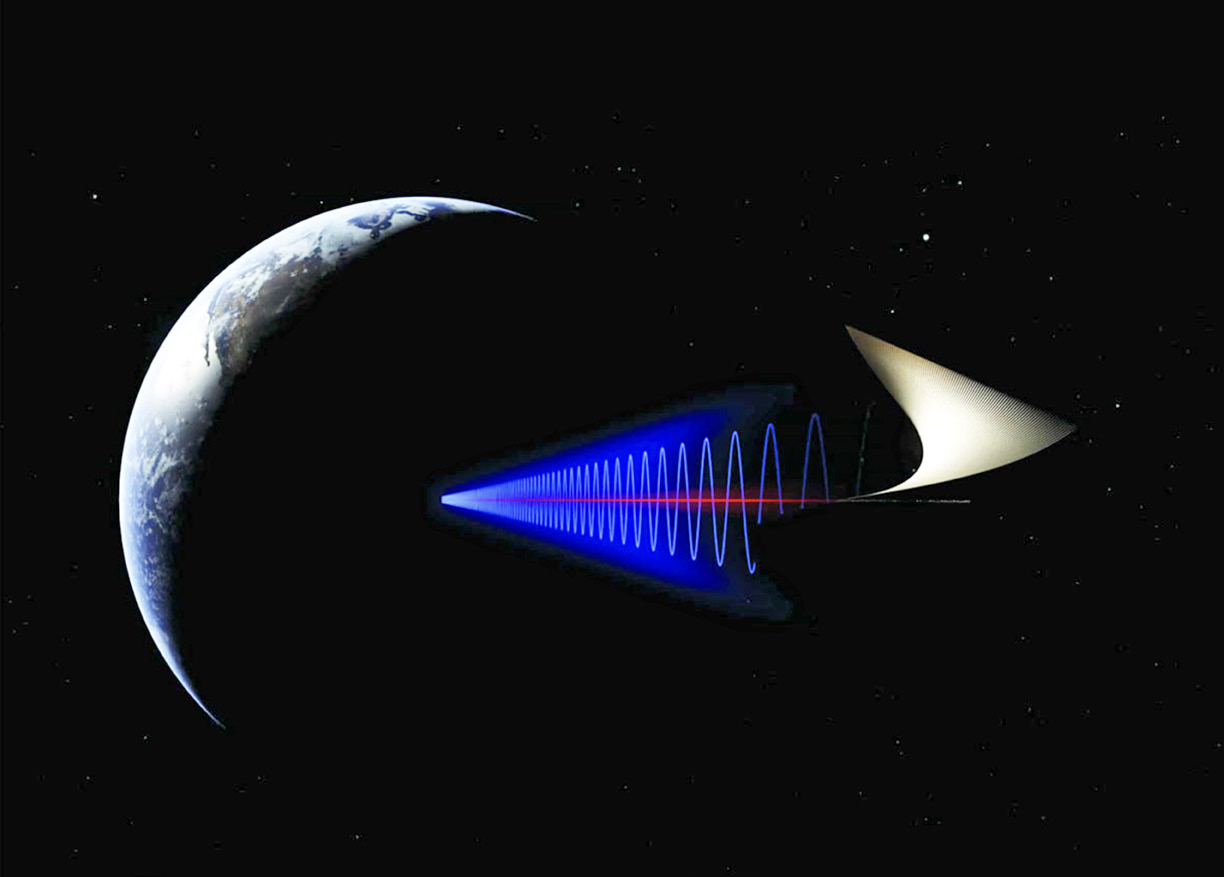

At its core, SBSP involves four main steps:

► Collecting solar energy in space

► Transmitting that energy back to Earth stations via microwave or laser technologies

► Converting that energy to electricity

► Delivering it to the grid or to batteries for storage

Since its inception in 1968, SBSP has been alternatively promoted as a transformative solution to the global renewable energy crisis and dismissed as science fiction confined to the realm of Gerard K. O’Neill’s The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. Proponents claim that SBSP could tap an inexhaustible energy source to supply electricity at competitive prices with fewer emissions than ground-based renewables; skeptics counter that SBSP still lacks a clear path to viability and could divert billions from proven terrestrial solutions while introducing new environmental risks.

Each of these technical steps, particularly the beaming of concentrated energy to Earth, introduces distinctive safety, regulatory, and liability challenges that go far beyond those faced by terrestrial power systems. But the market for SBSP is growing,1 and its unique operational environment—particularly the use of high-powered microwave or laser technologies to transmit energy from space to Earth—presents novel questions of potential harm, legal liability, and contractual risk allocation.

A misdirected or misused energy beam could damage infrastructure, injure people, or disrupt ecosystems, yet determining responsibility in such scenarios is complicated by the fact that space activities are governed by a patchwork of international treaties and national laws tied to the launching state of the space object, as well as telecommunications and energy regulations.

Navigating these overlapping regimes is essential, as contractual risk-shifting provisions in SBSP projects can either expose parties to—or shield them from—liability in ways that diverge considerably from traditional terrestrial frameworks.

__________________________________

Liability Frameworks

and Risk Shifting in Space

__________________________________

International Liability Framework

The concept of liability in space activities is crucial, particularly as commercial ventures expand. As space exploration has historically been viewed as a governmental domain, the existing treaties do not allow non-state actors such as companies or individuals to file claims directly against one another for damages.

Instead, governments are internationally responsible for space objects launched from their territory or by their nationals and may, at their discretion, seek to recoup damages from private actors under their domestic laws.

Two treaties form the backbone of international liability rules for space activities: the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and the 1972 Space Liability Convention.

The Outer Space Treaty, negotiated during the Cold War, declares that space activities must benefit all countries, forbids any nation from claiming sovereignty over outer space, and makes each country responsible for the activities of its citizens.

The Space Liability Convention builds on this by requiring that a country launching a space object, or the country whose territory is used for launch, compensate for any damage that object causes. If the damage occurs on Earth or to an aircraft—say, a deorbiting satellite strikes a building—the launching country is “absolutely liable,” meaning it must pay regardless of fault. If the damage occurs in space (e.g., one satellite colliding with another) liability is based on fault. The United States has ratified both treaties which, together, form the core of its international obligations.

While this framework seems straightforward when the harm involves physical impact, SBSP introduces more ambiguous and nuanced scenarios—especially where damage results from radiation or harmful interference rather than a “space object.”2

Moreover, if a high-powered laser beam causes a ground fire or blindness, pinpointing which SBSP actor caused the harm could be prohibitively costly or even impossible—and the treaties themselves do not set out how such fact-finding should occur or what evidentiary standard applies.

Because national governments are ultimately responsible for resolving disputes, each must decide how—and to what extent—to “flow down” liability for incidents involving space objects launched by commercial actors from its territory.

Striking the correct balance—protecting public funds while fostering private investment and innovation—is key to building a sustainable and innovative space ecosystem.

________________________________

Liability Frameworks

and Red Shifting in Space

________________________________

U.S. Liability Framework

In the United States, the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984 establishes a liability framework that allocates liability risk between the U.S. government and private actors involved in space activities.

Under the statute, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grants licenses for launching space objects, and its regulations provide for (i) cross-waivers of claims among all launch commercial participants, obligating each to be responsible for its own employees and property, regardless of fault; (ii) mandatory insurance coverage; and (iii) government indemnification for certain catastrophic losses exceeding the insured amount, recognizing that some risks may be uninsurable.3

This mandatory insurance regime and liability cap is intended to incentivize private parties to mitigate risk as much as possible by ensuring that they bear at least some damages caused by their activities, while also recognizing the high-risk nature of space and the potential for unforeseen events that could give rise to liability that would be difficult to otherwise address.

The Role of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

The FCC, in its capacity as the regulatory body responsible for managing commercial access to radio spectrum—i.e., the radio frequency (RF) portion of the electromagnetic spectrum4 that enables the wireless transmission of audio signals (voice), video signals (video), and digital signals (data)—plays a role in the SBSP regulatory regime.

SBSP operators will face FCC regulation when using the RF spectrum for satellite control links and—if applicable—microwave power transmission to Earth. FCC licenses are required for assigned frequencies, and licensees must comply with technical and operational rules designed to prevent harmful interference. Under the FCC’s liability standard, causing interference to other licensed services, even unintentionally, can trigger mandatory mitigation obligations, fines, or license revocation.

______________________________________

Best Practices for Space-Based

Solar Power Companies

______________________________________

SBSP developers can leverage existing liability-limiting statutes for space activities, but they must also prepare for operational and regulatory risks unique to the process of beaming energy from orbit to Earth. More, because the statutory cross-waiver applies only to personal injury and property damage, SBSP operators should expressly consider and allocate any additional risks through tailored indemnities, specialized insurance coverage, and robust technical safeguards.

The following practices can help maximize legal protections while supporting safe, commercially viable deployment.

First, it is crucial to draft contracts that include necessary liability cross-waiver provisions from the very beginning. Incorporating these clauses from the start in product development and business planning ensures they are already in place when applying for an FAA license, avoiding a last-minute scramble to insert them into existing agreements.

Second, SBSP operators should begin the process to obtain all necessary licenses from launch to the decommissioning of SBSP as early as possible. The FCC’s licensing process in particular could take more than nine months, particularly in instances where operators are seeking a license for a novel type of operation. Operators and investors should factor in delays for licensing approvals into their investment calculations. SBSP contracts should also expressly address and allocate liability for regulatory non-compliance and inquiries, particularly with respect to violations of spectrum allocation rules, environmental limits on electromagnetic emissions, and RF interference.

Finally, operators should also consider establishing a crisis communication team to address any reputational harm or public relations fallout should a tort occur in relation to the SBSP system because the public may perceive gross negligence on the part of the company if reasonable mitigation procedures were not followed.

All in all, the potential viability of SBSP could transform global energy security. However, to ensure both its feasibility and long-term sustainability in a market-driven environment, operators and investors must weigh regulatory requirements alongside economic considerations.

Mapping the liability landscape—and understanding how it intersects with technical, contractual, and operational realities—is not merely a legal exercise but a prerequisite for building a commercially viable SBSP enterprise that can endure in the competitive energy sector.

References

1 Global Market Insights, Space-Based Solar Power Market Size (estimating that the value of the global SBSP market share will reach 6.6 billion USD by 2034, (Dec. 2025), gminsights.com/industry-analysis/space-based-solar-power-market.

2 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, art. II, Mar. 29, 1972, 24 U.S.T. 2389, 961 U.N.T.S. 187 (defining the term “space object” to include “component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof.”)

3 See 51 U.S.C. § 50914(a)(3) (licensees are required to obtain insurance or demonstrate financial responsibility of at least $500 million to cover tort claims made by third parties, and $100 million for claims made by the U.S. government for damage or loss to government property, although these numbers can be adjusted by the Secretary of Transportation depending on market conditions).

______________________________________

Curt Blake

Author Curt Blake, Senior Columnist to SatNews Publishers, is Senior Of Counsel at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati. He is an attorney and senior executive with more than 25 years of experience leading organizations in high-growth industries— and more than 10 years as the CEO of Spaceflight, Inc.—at the forefront of the New Space revolution. Curt has extensive expertise in strategic planning, financial analysis, legal strategy, M&A, and space commercialization, with deep knowledge about the unique challenges of New Space growth and the roadmap to success in that ecosystem.

The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author himself and do not necessarily reflect the views of his employer or its clients.